Servo is a greenfield web browser engine that supports many platforms. Automated testing for the project requires building Servo for all of those platforms, plus several additional configurations, and running nearly two million tests including the entire Web Platform Tests. How do we do all of that in under half an hour, without a hyperscaler budget for compute and an entire team to keep it all running smoothly, and securely enough to run untrusted code from contributors?

We’ve answered these questions by building a CI runner orchestration system for GitHub Actions that we can run on our own servers, using ephemeral virtual machines for security and reproducibility. We also discuss how we implemented graceful fallback from self-hosted runners to GitHub-hosted runners, the lessons we learned in automating image rebuilds, and how we could port the system to other CI platforms like Forgejo Actions.

This is a transcript post for a talk I gave internally at Igalia.

Let's talk about how Servo can have fast CI for not a lot of money.

Servo is a greenfield web browser engine. And being a web browser engine, it has some pretty demanding requirements for its CI setup.

We have to build and run Servo for many platforms, including three desktop platforms and two mobile platforms.

We have to run many, many tests, the main bulk of which is the entire Web Platform Tests suite, which is almost 2 million subtests. We also have several smaller test suites as well, like the WebGPU tests and the DevTools tests and so on.

We have to build Servo in many different configurations for special needs. So we might build Servo with the oldest version of Rust that we still support, just to make sure that still works. We might build Servo as a library in the same way that it would be consumed by embedders. We have to lint the codebase. We have to build with optimizations for nightly and monthly releases. We have to build with other optimizations for benchmarking work, and so on.

And as you'll see throughout this talk, we do this on GitHub and GitHub Actions, but GitHub Actions is a very frustrating CI service, and it has many baffling limitations. And as time goes on, I think Servo being on GitHub and GitHub Actions will be more for the network effects we had early on than for any particular merits of these platforms.

On GitHub Actions, GitHub provides their own first-party runners.

And these runners are very useful for small workloads, as well as the logic that coordinates workloads. So this would include things like taking a tryjob request for "linux", and turning that into a run that just builds Servo for Linux. Or you might get a try job request for "full", and we'll turn that into a run that builds Servo for all of the platforms and runs all of the tests.

But for a project of our scale, these runners really fall apart once you get into any workload beyond that.

They have runners that are free of charge. They are very tiny, resource constrained, and it seems GitHub tries to cram as many of these runners onto each server as they possibly can.

They have runners that you can pay for, but they're very very expensive. And I believe this is because you not only pay a premium for like hyperscaler cloud compute rates, but you also pay a premium on top of that for the convenience of having these runners where you can essentially just flip a switch and get faster builds. So they really make you pay for this.

Not only that, but using GitHub hosted runners you can't really customize the image that runs on the runners besides being able to pull in containers, which is also kind of slow and not useful all the time. If there are tools and dependencies that you need that aren't in those images, you need to install them every single time you run a job or a workflow, which is such a huge waste of time, energy, and money, no matter whose money it is.

There are also some caching features on GitHub Actions, but they're honestly kind of a joke. The caching performs really poorly, and there's not a lot you can cache with them. So in general, they're not really suitable for doing things like incremental builds.

So we have all these slow builds, and they're getting slower, and we want to make them faster. So we considered several alternatives.

The first that comes to mind are these third-party runner providers. These are things like Namespace, Warpbuild, Buildjet. There's so many of them. The caveat with these is that they're almost always... almost as expensive per hour as GitHub's first-party runners. And I think this is because they try to focus on providing features like better caching, that allow you to accumulate less hours on their runners. And in doing so, they don't really have any incentive to also compete on the hourly rate.

There is one exception: there's a system called RunsOn. It's sort of an off-the-shelf thing that you can grab this software and operate it yourself, but you do have to use AWS. So it's very tightly coupled to AWS. And both of these alternatives, they often lack support for certain platforms on their runners. Many of them are missing Windows or missing macOS or missing both. And RunsOn is missing macOS support, and probably won't get macOS support for the foreseeable future.

We considered offloading some of the work that these free GitHub hosted runners do onto our own servers with, let's call them like, "proxy jobs". The idea would be that you'd still use free GitHub hosted runners, but you'd do the work remotely on another server. The trouble with this is that then you're still using these free GitHub hosted runners, which take up your quota of your maximum concurrent free runners.

And it's also tricky to do this without losing access to the broader ecosystem of prebuilt Actions. So these Actions are like steps that you can pull in that will let you do useful things like managing artifacts and installing dependencies and so on. But it's one thing to say, okay, my workload is this shell script, and I'm going to run it remotely now. That's easy enough to do, but it's a lot harder to say, okay, well, I've got this workflow that has a bunch of scripts and a bunch of external Actions made by other people, and I'm going to run all of this remotely. I'm going to make sure that all of these Actions are also compatible with being run remotely. That's a lot trickier. That said, you should probably avoid relying too heavily on this ecosystem anyway. It's a great way to get locked into the platform, and working with YAML honestly really sucks.

So we could set up an entire CI service. There are some CI services like Jenkins, Bamboo... honestly, most CI services nowadays have support for built-in container orchestration. So they can spin up containers for each runner, for each job, autonomously. And while they can do containers, none of them have really solved the problem of virtual machine orchestration out of the box. And this is a problem for us, because we want to use virtual machines for that security and peace of mind, which I'll explain in more detail a little bit later. And seeing as we lack the dedicated personnel to operate an entire CI service and have that be on the critical path — we didn't want to have someone on call for outages — this was probably not the best option for us at the moment.

What we decided to do was set up some self-hosted runners.

These solve most of our problems, primarily because we can throw as much hardware and resources at these runners as we want. We can define the contention ratios.

And better yet, we can also customize the images that the runners use. By being able to customize the runner images, we can move a lot of steps and a lot of work that used to be done on every single workflow run, and do it only once, or once per build. We only rebuild the runner images, say, once a week. So that significantly saves... it cuts down on the amount of work that we have to do.

This is not just installing tools and dependencies, but it's also enabling incremental builds quite powerfully, which we'll see a little bit later on.

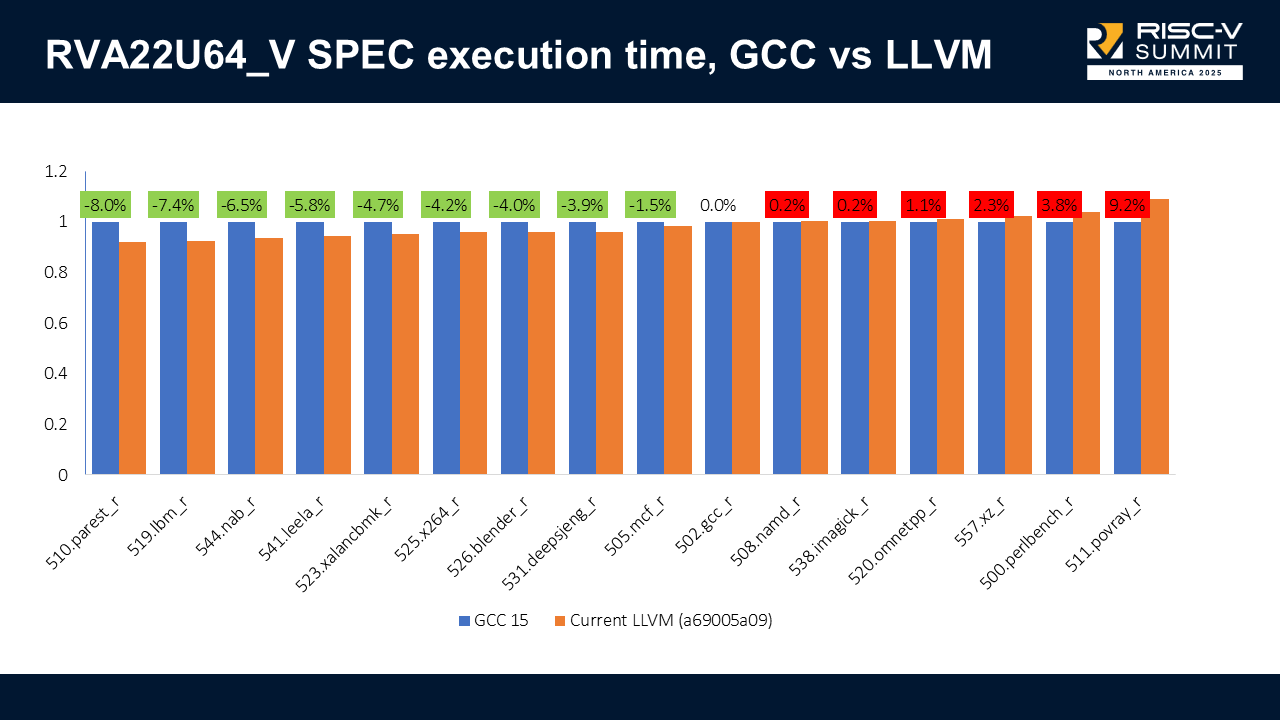

How much faster is this system with the self-hosted runners? Well, it turns out, quite a lot faster.

We've got this typical workflow that you use when you're testing your commits, when you're making a pull request. And if you kick off a tryjob like this, several of the jobs that we've now offloaded onto self-hosted runners are now taking 70, 80, even 90% less time than they did on GitHub hosted runners, which is excellent.

And even for the web platform tests, we found more modest time savings with the capacity that we've allocated to them. But as a result, even though the savings are a bit more modest, what's worth highlighting here is that we were able to go from twenty runners — we had to parallelise this test suite across twenty runners before — and now we only need three.

Some things that make our system unique and that we're pretty proud of — and these things apply to all versions of our system, which we've been developing over the last 12 to 18 months.

The first is that we build on top of the native CI service of the Git forge. So in this case, it's GitHub and GitHub Actions. It could be Forgejo and Forgejo Actions in the future, and we're working on that already.

We also want to give users more or less a transparent user experience, the idea being that users should not notice any changes in their day-to-day work, besides the fact that their builds have gotten faster. And I think for the most part, we have achieved that.

Our system supports all of the platforms that GitHub Actions supports for their runners, including Linux, Windows, and macOS, and we could even support some of the other platforms that Forgejo Actions supports in the future, including BSD.

We have the ability to set up a job so that it can try to use self-hosted runners if they're available, but fall back to GitHub hosted runners if there's none available for whatever reason, like maybe they're all busy for the foreseeable future, or the servers are down or something like that. We have the ability to fall back to GitHub hosted runners, and this is something that was quite complicated to build, actually. And we have a whole section of this talk explaining how that works, because this is something that's not actually possible with the feature set that GitHub provides in their CI system.

It's secure enough for a large public project like Servo, where we don't necessarily know all of our contributors all that well personally. And this is in large part because we use virtual machines, instead of just containers, for each run and for each job. My understanding is that it is possible to build a system like this securely with containers, but in practice it's a lot harder to get that right as a security boundary than if you had the benefit of a hypervisor.

And of course it is all completely self-hosted, which makes it about as cheap as it gets, because your operating expenses are really just the costs of bare metal compute.

Now, how cheap is that? Well, in our deployment in Servo, we spend about 300 EUR per month on servers that do general-purpose runners, and these handle most of our workload.

If we were to compare that to if we were running on GitHub-hosted runners, there'd be almost an order of magnitude increase in costs, somewhere like 1400 EUR to over 2000 EUR per month if we were doing the same work on GitHub-hosted runners.

There are also significant increases if we went with third-party runner providers as well, although not quite as much.

But in truth, this is actually kind of an unfair comparison, because it assumes that we would need the same amount of hours between if we were running on self-hosted runners or if we were running on GitHub hosted runners. And something that you'll see throughout this talk is that this is very much not the case. We spend so many fewer hours running our jobs, because we have to do so much less work on them. So in reality, the gap between our expenses with these two approaches would actually be a lot wider.

There are three ways to use our CI runner system.

The first one is the way that GitHub designed self-hosted runners to be used. The way they intend you to use self-hosted runners is that when you define a job, you use this runs-on setting to declare what kind of runners your job should run on. And you can use labels for GitHub hosted runners, or you can define arbitrary labels for your own runners and select those instead. But you have to choose one or the other in advance. And if you do that, you can't have any kind of fallback, which was a bit of a drawback for us, especially early on. One benefit of this, though, is that you get the natural ability to queue up jobs. Because if, at the time of queuing up a new job, if there's no self-hosted runners available yet, the job will stay in a queued state until a self-hosted runner becomes available. And it's nice that you essentially get that for free. But you have no ability to have this kind of graceful fallback.

So we built some features to allow you to do graceful fallback. And how this works is that each of the servers that operates these runners has a web API as well. And you can hit that web API to check if there are runners available and reserve them. Reserving them is something you have to do if you're doing graceful fallback. But I'll explain that in more detail a bit later on. And in doing so, because you have a job that can check if there are runners available, you can now parameterize the runs-on setting and decide "I want to use a self-hosted runner, or a GitHub hosted runner". It's unclear if this is going to be possible on Forgejo Actions yet, so we may have to add that feature, but it's certainly possible on GitHub Actions.

Now, the downside of this is that you do lose the ability, that natural ability, to queue up jobs, and I'll explain why that is a bit later. But in short, we have a queue API that mitigates this problem, because you can hit the queue API, and it can have a full view of the runner capacity, and either tell you to wait, or forward your request once capacity becomes available.

Some things that you can do with our system, that you can't do with GitHub hosted runners. One of them is check out the repo significantly faster.

Something about GitHub Actions and how it works is that, if you run a job, you run a workflow in a repo, you don't actually get a checkout of the repo. You don't get a clone of the repo out of the box, unless you explicitly add a step that does a checkout. And this is fine for the most part, it works well enough for most users and most repos.

But the Servo repo has over 130,000 files across 6,000 directories, and that's just the tracked files and directories. And as a result, even if we use things like shallow clones, there's just kind of no getting around the fact that cloning this repo and checking it out is just slow. It's unavoidably slow.

And it's especially slow on Windows and macOS, where the filesystem performance is honestly often pretty poor compared to Linux. So we want to make our checkouts faster.

Well, what we can do is, we can actually move the process of cloning and checking out the repo from the build process, and move that into the image build process. So we only do it once, when we're building the runner images.

Then what we can do is go into the jobs that run on self-hosted runners, and switch out the stock checkout action with our own action. And our own action will just use the existing clone of the repo, it will fetch the commit that we actually need to build on, then switch to it, and check it out.

And as a result, we can check out the Servo repo pretty reliably in a couple of seconds, instead of having to check out the entire repo from scratch.

Something that flows on from that, though, is that if we are baking a copy of the Servo repo into our runner images, well, what if we just bake a copy of the built artifacts as well? Like, why don't we just build Servo, and bake that into the image?

And this will allow us to do incremental builds, because Servo is a Rust project, and we use Cargo, and Cargo supports incremental builds. As a result, by doing this, when you run a job on our CI system, most of the time we only have to rebuild a handful of crates that have changed, and not have to rebuild all of Servo from scratch.

Now, this is not perfect. Sometimes we'll have some compilation units that get falsely rebuilt, but this works well enough, for the most part, that it's actually a significant time savings.

I also probably wouldn't trust this for building artifacts that you actually want to release in a finished product, just because of the kinds of bugs that we've seen in Cargo's incremental build support.

But for everything else, just your typical builds where you do like commit checks and such, this is very very helpful.

Servo has this system deployed, and it's had it deployed for at least the last year or so.

Nowadays we have three servers which are modestly large, and we use these for the vast majority of our workload. We also have two smaller servers that we use for specific benchmarking tasks.

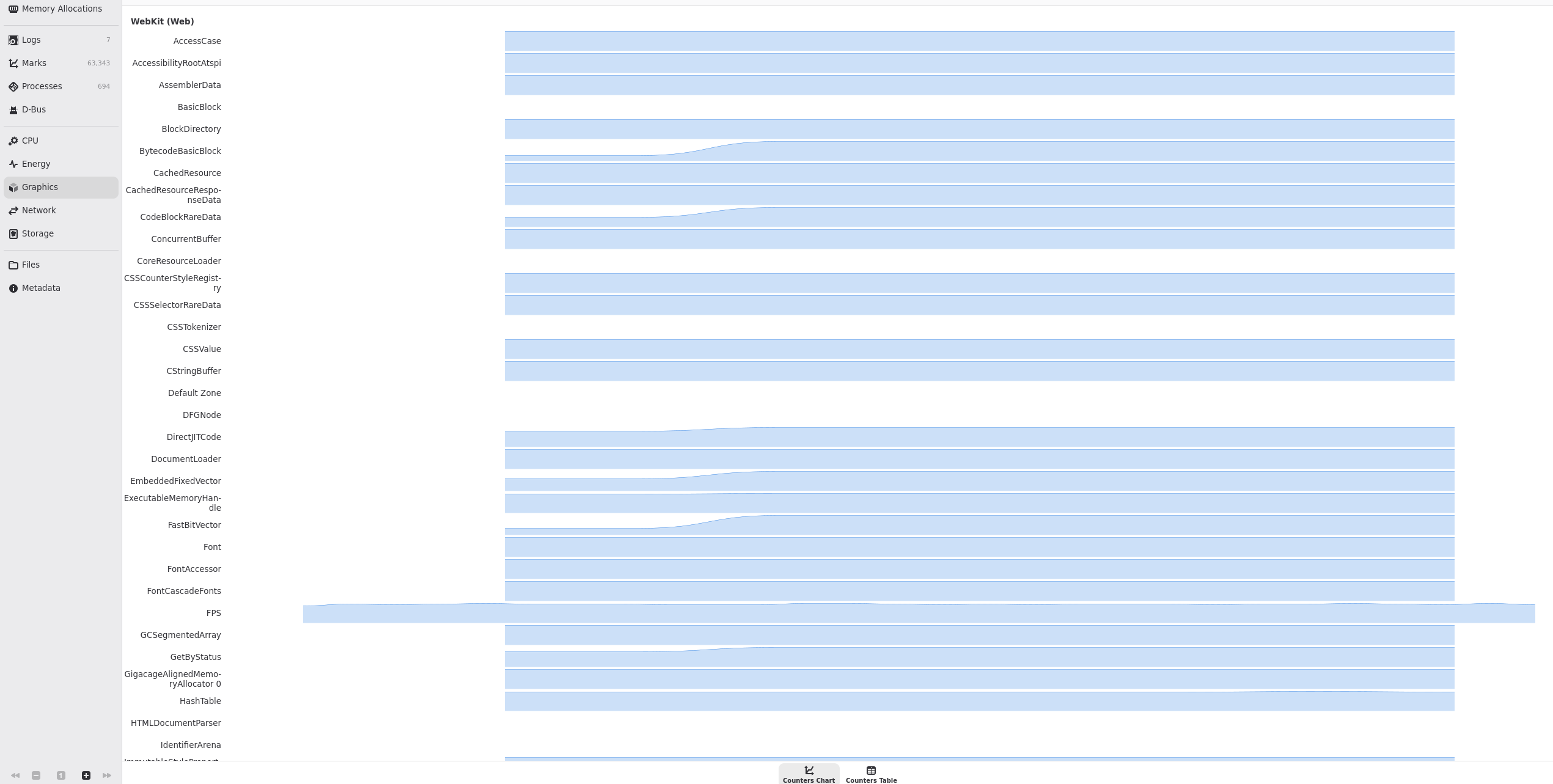

The stack on these servers, if you could call it that, is largely things that I personally was very familiar with, because I built this. So we've got NixOS for config management, the hypervisor is libvirt and Linux KVM, and the storage is backed by ZFS. The process of actually building the images, and managing the lifecycle of the virtual machines though, is done with some custom orchestration tooling that we've written.

This tooling consists of two services. The monitor service, which runs on every server that operates self-hosted runners, and the queue service, which is single and global.

So the monitor service does the vast majority of the work. It rebuilds virtual machine images, these templates. It clones the templates into virtual machines for each runner, for each job. It registers the runners with the CI service using its API, so that it can receive jobs. And it can also label the runners to tie them to specific jobs when asked to reserve them. This is optional, but it is a required step if we're doing graceful fallback.

Now, with graceful fallback, you do lose the ability to naturally queue up jobs. So what we've put on top of that is a single queue service that sits in front of the cluster, and it essentially acts as a reverse proxy. It's quite thin and simple, and there's a single one of them, not one per server, for the same reason as the general principle of, like, when you go to a supermarket, it's more efficient to have a single large queue, a single long queue of customers that gets dispatched to a bunch of shopkeepers. That's more efficient than having a sort of per-shopkeeper queue, especially when it comes to, like, moving jobs dynamically in response to the availability.

So we've got a whole section here about how graceful fallback works. I might cut this from shorter versions of the talk, but let's jump into it.

On GitHub Actions, every job has this runs-on setting, that defines what kind of runner it needs to get assigned to. It has to define this in advance, before the job runs.

And annoyingly, once you choose, "I want to run on a GitHub hosted runner" or "I want to run on a self-hosted runner", once you decide that, there's no turning back. Now, if you've decided that my job needs to run on a self-hosted runner, it can only run on a self-hosted runner. And now the outcome of your job, and the outcome of your workflow, now depends on that job actually getting a self-hosted runner with the matching criteria and succeeding. There's no way for that to become optional anymore.

And you might say, okay, well, maybe I can work around this by spinning up my self-hosted runners, but just giving them the same labels that GitHub assigns to their runners, maybe it'll do something smart? Like maybe... it will run my self-hosted runners if they're available and fall back. But no, the system has no sense of priority and you can't even define any sense of priority of like, I want to try this kind of runner and fall back to another kind of runner. This is simply not possible with the GitHub Action system.

So it may seem like it's impossible to do graceful fallback, but we found a way.

![Decision jobs

- Prepend a job that chooses a runner label

1. let label = runner available?

| yes => [self-hosted label]

| no => [GitHub-hosted label]

2. $ echo](https://www.azabani.com/images/servo-ci/mpv-shot0048.jpg)

[self-hosted label]

| no => [GitHub-hosted label]

2. $ echo " /> [self-hosted label]

| no => [GitHub-hosted label]

2. $ echo " /> [self-hosted label]

| no => [GitHub-hosted label]

2. $ echo "label=${label}" | tee -a $GITHUB_OUTPUT

- Use the step output in runs-on

runs-on: ${{ needs.decision.outputs.label }}

- But two decisions must not be made concurrently">

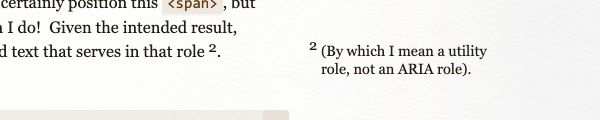

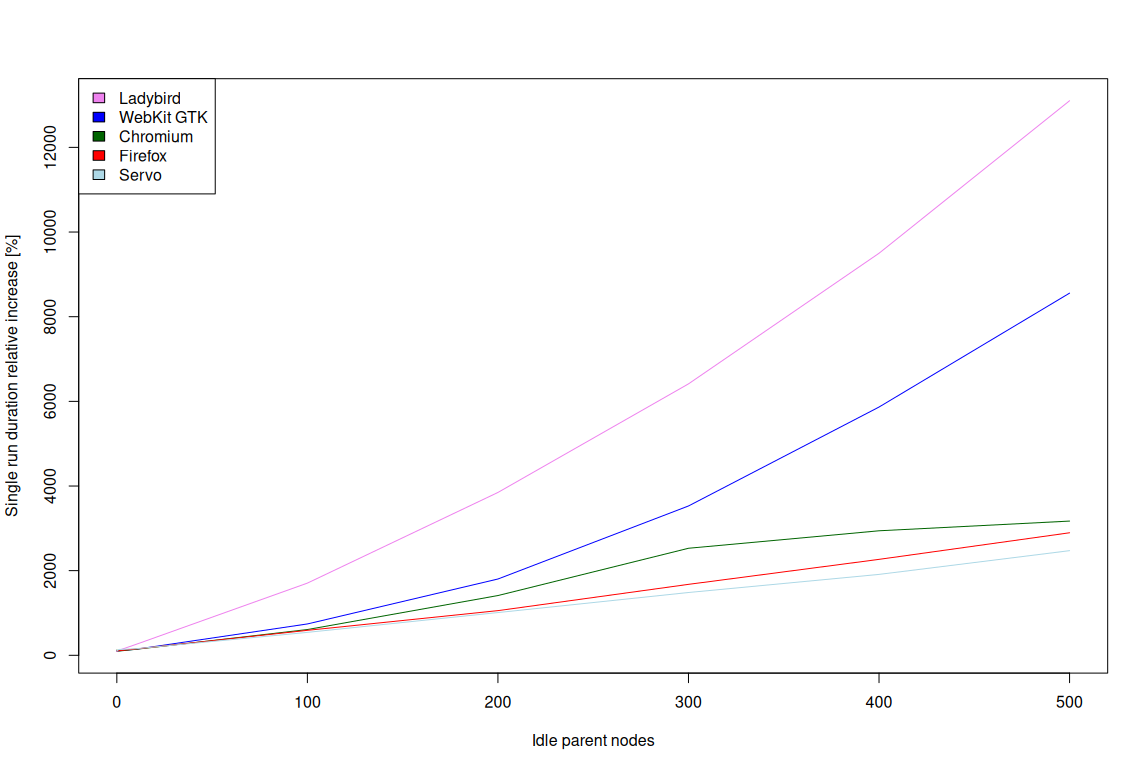

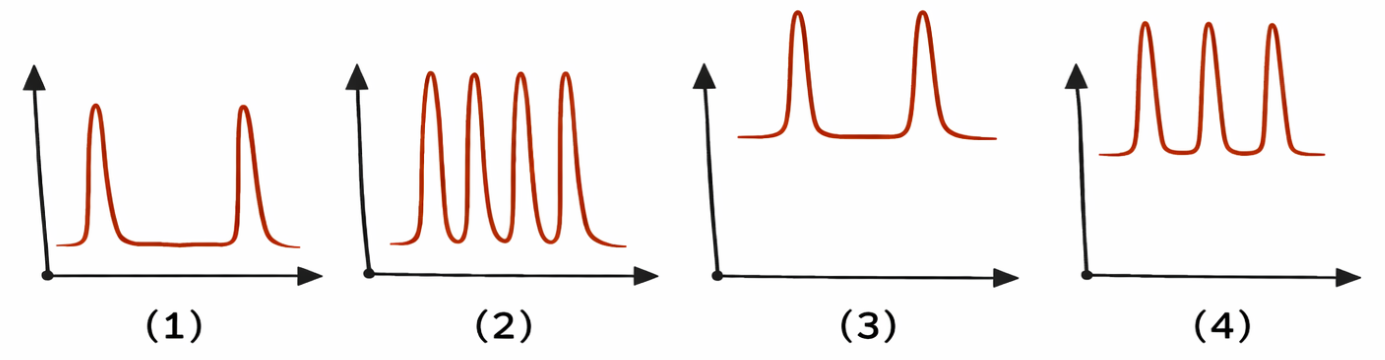

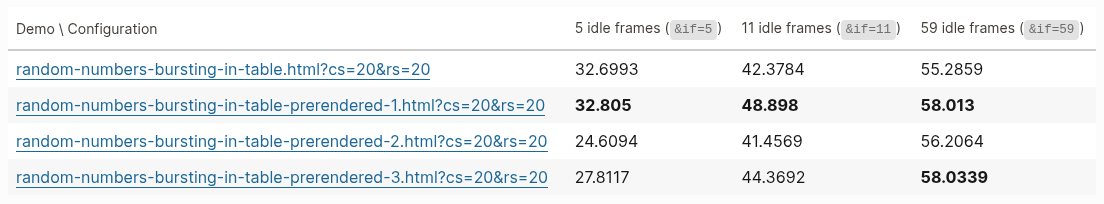

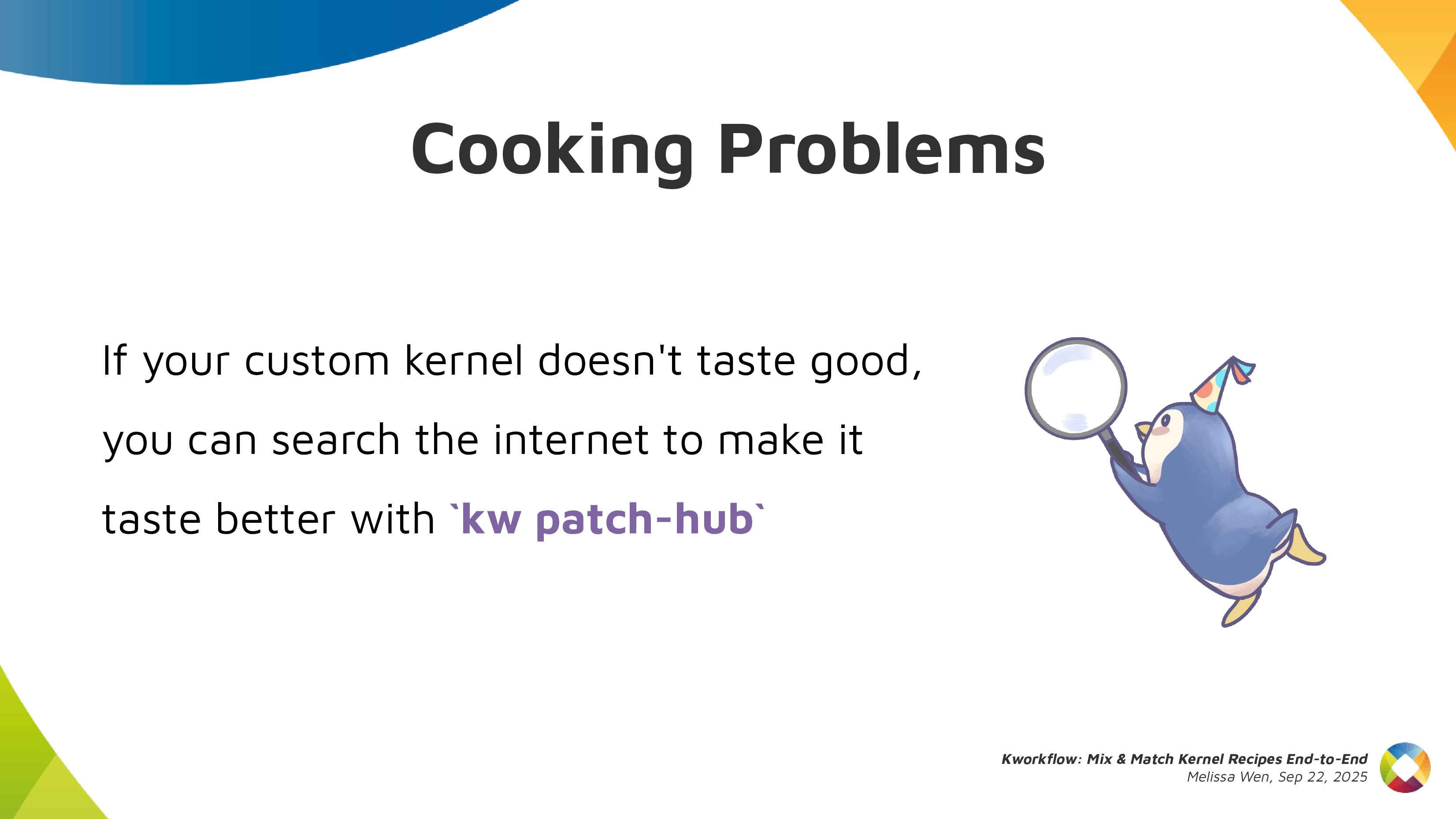

What we can do is add a decision job, for each workload job that may need to run on self-hosted runners. And we prepend this job, and its job is to choose a runner label.

So how it essentially works is: it checks if a runner is available, and based on that, either chooses a self-hosted label or a GitHub hosted label. And it chooses it and sets it in an output. And this output can get pulled in... in our workload job, the job that actually does our work, because now you can parameterize the runs-on setting, so that it takes the value from this previous decision job.

Unfortunately, it seems like this may not be possible in Forgejo Actions just yet, so we might have to develop support for that, but it's certainly possible in GitHub Actions today, and it has been for quite a while.

The one caveat with this approach is that you need to be careful to only do this decision process one at a time. You should not do two instances of this process concurrently and interleave them.

- runs-on: ${{ needs.decision.outputs.label }}

runs-on: 6826776b-5c18-4ef5-8129-4644a698ae59

- Initially do this directly in the decision job (servo#33081)" />

- runs-on: ${{ needs.decision.outputs.label }}

runs-on: 6826776b-5c18-4ef5-8129-4644a698ae59

- Initially do this directly in the decision job (servo#33081)" />

- runs-on: ${{ needs.decision.outputs.label }}

runs-on: 6826776b-5c18-4ef5-8129-4644a698ae59

- Initially do this directly in the decision job (servo#33081)">

The reason for this is something you'll see if you think about a lot of the answers that you get on Stack Overflow and the GitHub forums. If you look up, "how do I solve this problem? How do I define a job where I can fall back from self-hosted runners to GitHub hosted runners?"

And most of the answers there, they'll have a problem where they check if there are any runners that are available, and then, they will make the decision, committing to either a self-hosted runner or a GitHub hosted runner. The trouble is that in between, if another decision job comes in and tries to make the same kind of decision, they can end up "earmarking" the same runner for two jobs. But each runner is only meant to run one job, and it can only run one job, so one of the jobs will get left without a runner.

So we can start to fix this by actually reserving the runners when we're doing graceful fallback. And how we've done it so far, is that we've used the GitHub Actions API to label the runner when we want to reserve it, and we label it with a unique ID. Then the workload job can put that unique ID, that label, in its runs-on setting. Instead of a general runner label, it can tie itself to this specific, uniquely identified runner label.

And we did it this way initially, because it allowed us to do it inside the decision job, at first. I think in the future, we will have to move away from this, because on Forgejo Actions, the way runner labels work is quite different. They're not something that you can sort of update after the fact. In fact, they're actually kind of defined by the runner process. So this approach for reserving runners won't work on Forgejo Actions. We'll probably have to do that internally on the runner servers. But in the meantime, we use labeling. Yeah, so at first we did this inside the decision job.

There are some problems with this. One of them is that now the decision job has to have a GitHub token that has permissions to manage runners and update their labels. And this is something that we'd like to avoid if possible, because we'd like our jobs to have least privilege that they need to do their work.

And something I didn't mention is that reserving runners in this way doesn't actually solve the problem on its own, because you've now transformed the problem to being, okay, we're going to check if the runner is not yet reserved. We're going to check if there's an unreserved runner, and then, we're going to label the runner. But in between, there's a moment where another process doing the same thing could make the same decision. And as a result, if we just did this, we could end up with a situation where one runner gets assigned two unique labels, but it can only fulfill one of them. So we have that same problem again.

So you might say, okay, well, it looks like GitHub Actions has this neat job concurrency feature. I mean, they say you can use this to define a job in a way where only one of them will run at a time, and you can't run them concurrently, so let's try using that to solve this problem.

What you'll find, though, is that if you try to solve the problem with job concurrency, as soon as there's even the slightest bit of contention, you'll just have your runs starting to fail spuriously, and you'll have to keep rerunning your jobs, and it'll be so much more annoying.

And the reason for this is that, if you look more closely at the docs, job concurrency essentially has a queue limited to one job. So at a maximum, you can have one job, one instance of the job that's running, one instance of the job that's queued, and then if another instance of the job comes in while you have one running and one queued, then those extra jobs just get cancelled, and the build fails. So unfortunately, job concurrency does not solve this problem.

So to solve these problems, what we did is we moved that decision and runner reservation process out of the decision jobs, and into the servers that operate the runners themselves. And we do this with an API that runs on the servers.

One smaller problem you might notice though, is that there's still a possibility that you could reserve a runner, but then after you've reserved the runner, it might fail to actually run. And this has become a lot less likely in our system, in our experience nowadays, now that we've ironed out most of the bugs, but it can still happen from time to time, usually due to infrastructure or network connectivity failures.

And we wanted to solve this by setting a time limit on how long a job can be queued for, because if it can't actually get a runner in practice, it will get stuck in that queued state indefinitely. But unfortunately, while we can set a time limit on how long a job can run for once it's been assigned, we can't actually set a time limit on how long a job can be queued for.

So we have to rely on the default built-in limit for all jobs, where I think there's like a limit of a day or two? So like, 24 or 48 hours or so, for how long a job can be queued? And this is just a really long time. So as a result, whenever this happens, you essentially have to cancel the job manually, or if you don't have permission to do that, you have to go ask someone who has permission, to go and cancel your job for you, which is really annoying.

So we solved that using timeout jobs. A timeout job is a sibling to your workload job, and it acts like a watchdog, and it ensures that it actually got a runner when you expect to get a self-hosted runner.

And how that works is, we wait a short amount of time, just like a minute or two, which should be long enough for the runner to actually start running the job, and then we query the API of the CI service to check if the workload job actually started running, or if it's still in that queued state. If it's still queued after two minutes, we cancel the run.

Unfortunately, we can't just cancel the job run. We do have to cancel the whole workflow run, which is quite annoying. But, you know, it's GitHub, nothing is surprising anymore.

Thankfully, we only have to run this when we actually get a self-hosted runner, so we can make it conditional. But over time, in Servo's deployment, we have actually stopped using these, to free up some of those GitHub-hosted runner resources.

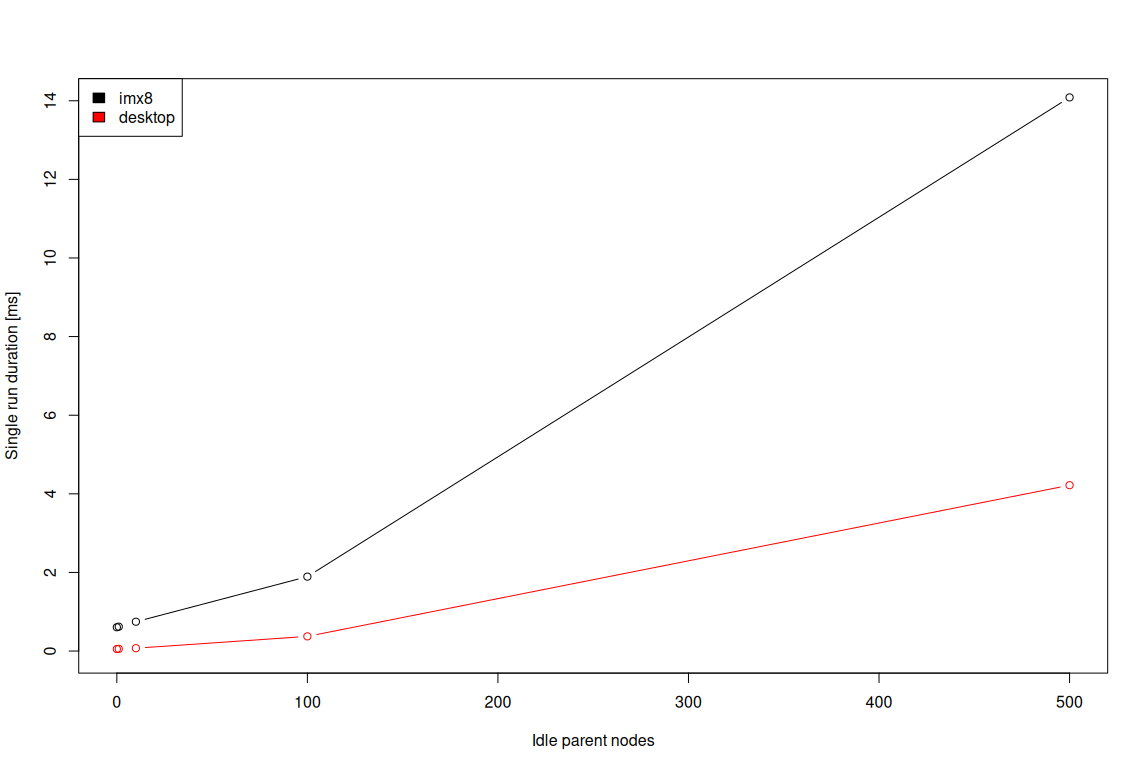

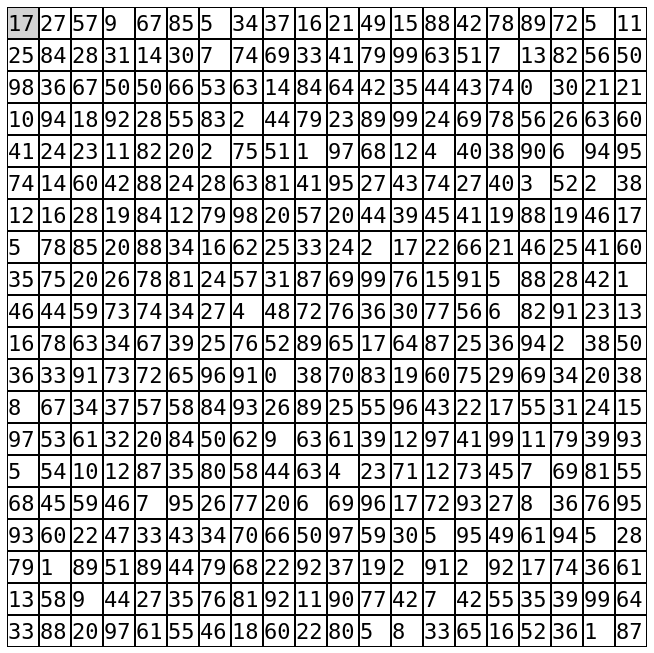

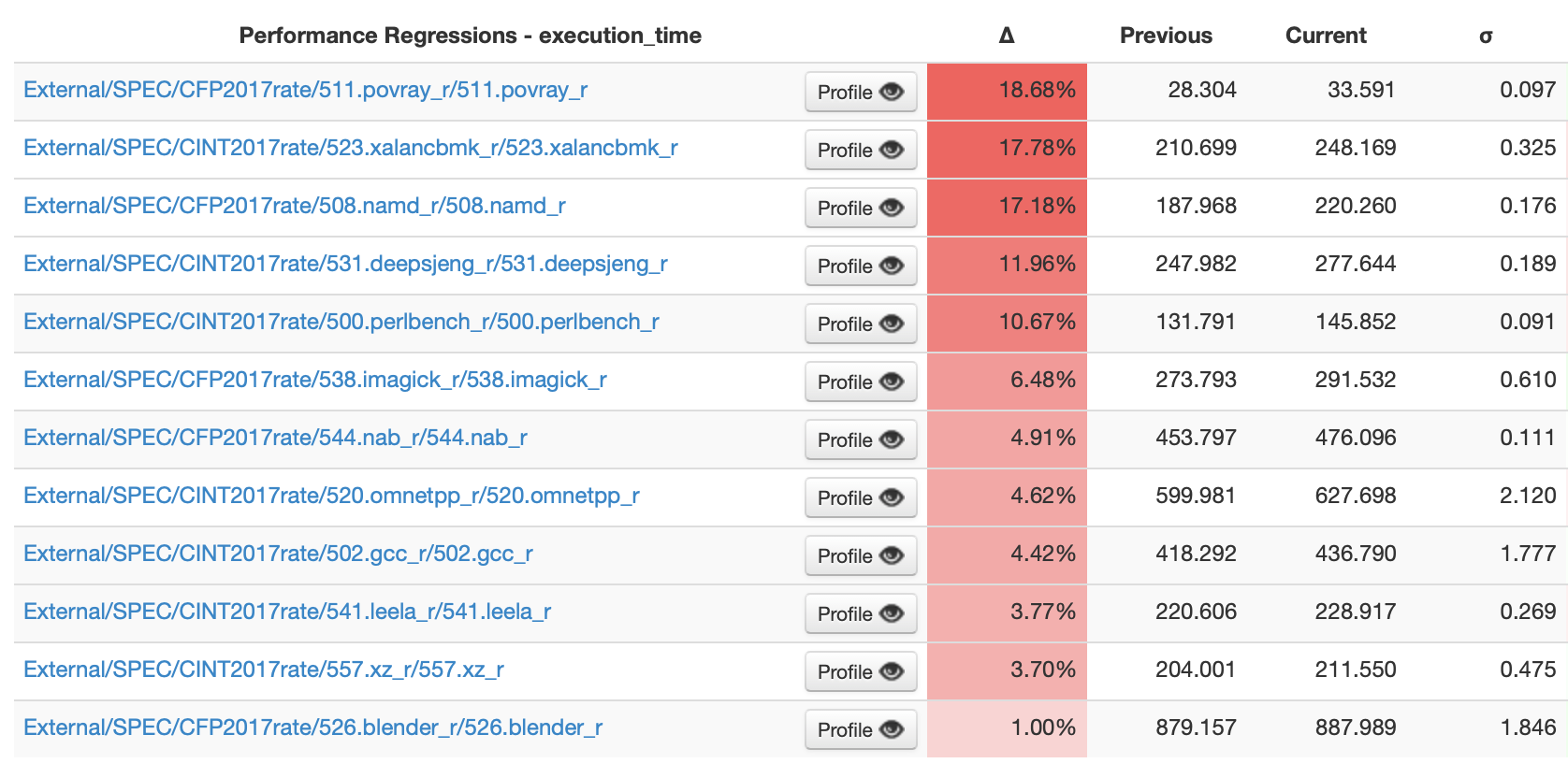

One challenge that comes in making these timeout jobs is identifying the workload jobs uniquely, so we can look up whether it's still queued or whether it's started running. There are unique IDs for each job run. These are just like an incrementing number, and you'd think we'd be able to use this number to look up the workload job uniquely and robustly.

Unfortunately, you can't know the run ID of the job [correction 2025-12-24] until it starts, and it may not ever start... or at least you may not know it until the workflow runs, and there can be many instances of the job in the workflow because of workflow calls. Workflow calls are a feature that essentially allows you to inline the contents of a workflow in another as many times as you like. And as a result, you can have multiple copies, multiple instances of a job that run independently within one workflow run. So we definitely need a way to uniquely look up our instance of the workload job.

The trouble is that the only job relationship you can do in GitHub Actions is a needs relationship, and that's inappropriate for our situation here, because we can say that the workload job needs the decision job, we can say the timeout job needs the decision job — and in fact we do both of these, we "need" to do both of these — but we can't say that the timeout job needs the workload job, because of how needs works.

How needs works is that if job A needs job B, then job B has to actually get assigned a runner, and run, and complete its run — it has to finish — before job A can even start. And in this situation, we're making a timeout job to catch situations where the workload job never ends up running, so if we expressed a needs relationship between them, then the timeout job would never run, in these cases at least.

And even if we could express a needs relationship between jobs, like maybe we could walk the job tree, and go from the timeout job, through the decision job via the needs relationship, and then walk back down to the workload job using the same kind of needs relationship... unfortunately, none of these needs relationships are actually exposed in the API for a running workflow. So like, they're used for scheduling, but when you actually go and query the API, you can't tell what job needs what other job. They're just three jobs, and they're unrelated to one another.

![Uniquely identifying jobs

- Tie them together by putting the <UUIDv4> in the name:

name: Linux [${{ needs.decision.outputs.unique-id }}]

name: Linux [6826776b-5c18-4ef5-8129-4644a698ae59]

- Query the CI service API for all jobs in the workflow run

- Check the status of the job whose name contains

[${{ needs.decision.outputs.unique-id }}]

- Yes, really, we have to string-match the name :)))](https://www.azabani.com/images/servo-ci/mpv-shot0054.jpg)

in the name:

name: Linux [${{ needs.decision.outputs.unique-id }}]

name: Linux [6826776b-5c18-4ef5-8129-4644a698ae59]

- Query the CI service API for all jobs in the workflow run

- Check the status of the job whose name contains

[${{ needs.decision.outputs.unique-id }}]

- Yes, really, we have to string-match the name :)))" /> in the name:

name: Linux [${{ needs.decision.outputs.unique-id }}]

name: Linux [6826776b-5c18-4ef5-8129-4644a698ae59]

- Query the CI service API for all jobs in the workflow run

- Check the status of the job whose name contains

[${{ needs.decision.outputs.unique-id }}]

- Yes, really, we have to string-match the name :)))" /> in the name:

name: Linux [${{ needs.decision.outputs.unique-id }}]

name: Linux [6826776b-5c18-4ef5-8129-4644a698ae59]

- Query the CI service API for all jobs in the workflow run

- Check the status of the job whose name contains

[${{ needs.decision.outputs.unique-id }}]

- Yes, really, we have to string-match the name :)))">

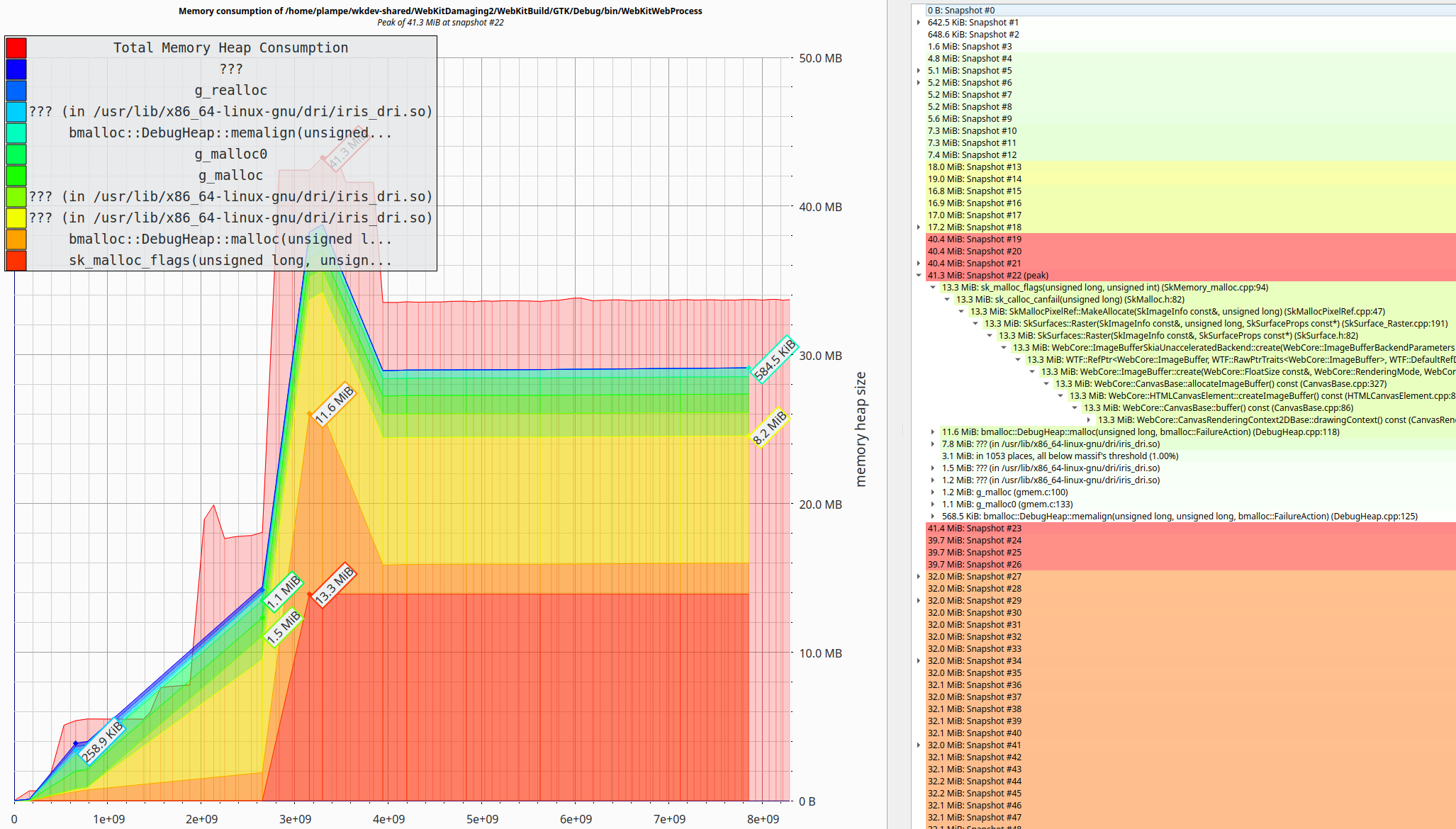

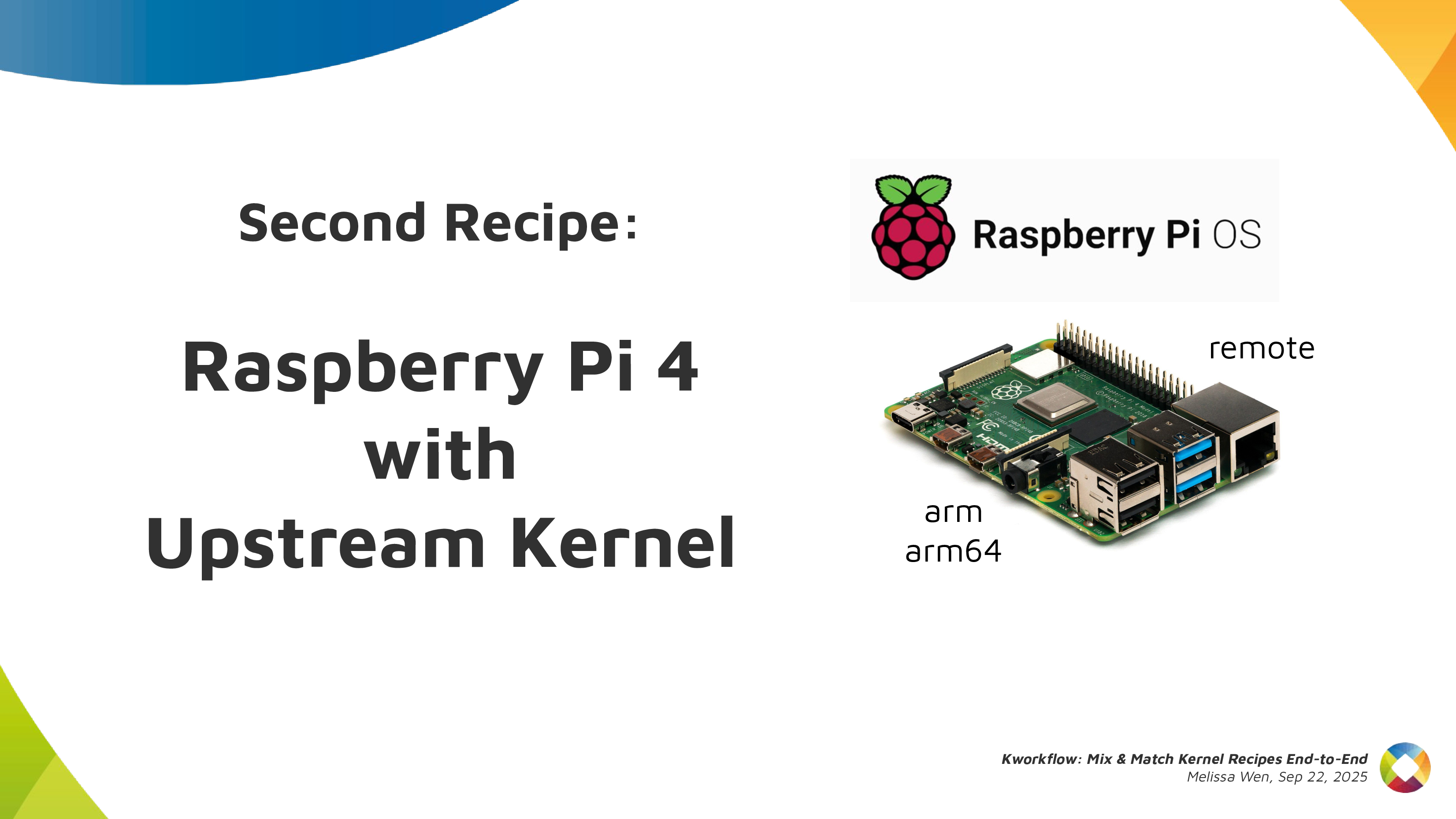

So how we had to end up solving this is, we had to tie these jobs together by generating a unique ID, a UUID, and putting it in the friendly name, like the display name of the job, like this.

And to query the CI service to find out if that job is still queued, we need to query it for the whole workflow run, and just look at all of the jobs, and then find the job whose name contains that unique ID.

Then we can check the status, and see if it's still queued. This is really, really silly. Yes, we really do have to string match the name, which is bananas! But this is GitHub Actions, so this is what we have to do.

One thing I didn't mention is that being able to reserve runners needs to be kind of a privileged operation, because we don't just want an arbitrary client on the internet to be able to erroneously or maliciously reserve runners. Even if they may not be able to do a whole lot with those runners, they can still deny service.

So to use the monitor API to do graceful fallback and to request and reserve a runner, normally we would require knowledge of some kind of shared secret, like an API token, and that's what we've done for most of the life of this system.

The trouble with this is that there are many kinds of workflow runs that don't have access to the secrets defined in the repo. A big one is pull_request runs. Most of the time, pull_request runs don't have access to secrets defined in the repo. And there is another kind of run called a pull_request_target run, and those do have access to secrets, but they also have some pretty gnarly security implications that mean that in general, you wanna avoid using these for pull requests anyway.

So if you're stuck with pull_request runs for your pull requests, does that mean that you can't use self-hosted runners? How do we allow pull_request runs to request and reserve runners in a way that it can prove that its request is genuine and authorized?

What we do is we use artifacts. We upload a small artifact that encodes the details of the request and publish the artifact against the run. So in the artifact, we'd say, "I want two Ubuntu runners" or "one Windows runner" or something like that.

And then we would hit the monitor API, we hit a different endpoint that just says, go to this repo, go to this run ID, and then check the artifacts! You'll see my request there! And this does not require an API token, it's not a privileged operation. What's privileged is publishing the artifact, and that's unforgeable; the only entity who can publish the artifact is the workflow itself.

All we have to do then, all we have to be careful to do, is to delete the artifact after we reserve the runner, so that it can't be replayed by a malicious client. And in the event that deleting the artifact fails, we can also set the minimum auto-delete period of, I think at the moment it's 24 hours, just in case that fails.

Graceful fallback normally means that you lose the ability to naturally queue jobs for self-hosted runners. And this happens because when you hit the API, requesting, you know, are there any available runners, please reserve one for me. If there aren't any available at the time of the request, we will immediately fall back to running on a GitHub hosted runner.

But the thing is, is that our self-hosted runners are generally so much faster! A GitHub hosted run might take five times as long as the equivalent self-hosted run, and if that was the case, it would actually be beneficial to wait up to 80% of that time, and we'd still probably save time.

So to increase the utilization of our self-hosted runners, what we can do is run a small queue service that sits in front of the monitors, and it essentially acts as a reverse proxy. It will take the same kind of requests for reserving runners as before, but it will have a global view of the availability and the runner capacity at any given moment.

And based on that, it will either respond to the client saying, go away and please try again later, or it will forward the request onto one of the monitors based on the available capacity.

We also have some lessons here about how to automate building virtual machine images, essentially. And these are lessons that we've learned over the last year or two.

GitHub Actions uses Packer for their first-party runner images, so they use Packer to build those images. And our monitor service also automates building the images, but we don't use Packer.

Initially, we had a handful of scripts that we just kicked off manually whenever we needed to update our images, but we've now fully automated the process. And we've done this using some modules in our monitor service, so there's some high-level Rust code that drives these image rebuilds, and it even uses reflink copies to take advantage of copy-on-write time savings and space savings with ZFS.

Now, one of the complications we ran into when building images, over the past year or so, is that we used to pull a sort of clever trick where, we would do as much of the process of configuring the virtual machine image on the host, actually, as possible, rather than doing configuration inside the guest, and having to spin up the guest so that we can configure it. And we were able to do this by essentially mounting the root file system of the guest image, on the host, and then injecting files, like injecting tools and scripts and other things that are needed by the image and needed to configure the image.

But we stopped being able to do this eventually because, well, essentially because of macOS. macOS has no file system that's usable for building Servo that can also be mounted on Linux with write support. Because like, just think about them, right? We've got HFS+, which Linux can write to but only if there's no journaling and you can't install macOS on HFS+ without journaling. There's APFS, which Linux has no support for. There's exFAT, which has no support for symlinks, so a lot of tools like uv will break. There's NTFS, which we thought would be our savior, but when we tried to use it, we ran into all sorts of weird build failures, which we believe are due to some kind of filesystem syncing race condition or something like that, so NTFS was unusable as well.

In the end, what we had to do is, if a guest image needed any tools or dependencies, it had to download them from a web server on the host.

We eventually settled on a consistent approach to automating the process of installing the OSes and configuring them for each runner template.

And the approach that we used was to install the OS using whatever method is easiest, and to bootstrap the config using any native config management system, if there is one included with the operating system.

But once we've kicked off that process, we then use the native config management as little as possible. And we do this because a lot of the config management tools that are built into these operating systems are quite quirky and annoying, and they are built for needs that we don't have, the primary need being that they can manage the configuration of a system over time, keeping it up to date with any changes. The thing about these runner images, though, is that each runner image only needs to get built once, it only needs to get configured once, and then after after that it'll be cloned for each runner, and then it will only run once, and this kind of sort of "one shot" use case is something that's kind of overkill with config management systems.

We can just do it with the usual scripting and automation facilities of the operating system. How does that look like in practice?

Well for Linux, we install the OS using pre-built Ubuntu cloud images, that we just download from the mirrors.

We bootstrap the config using cloud-init, which is such a painful... it's so painful to use cloud-init. We use it because it's included with the operating system, so that means it's the fastest possible way to get started.

We use it as little as possible: we just configure the logs to go to a TTY, we configure the network, so we can connect to the network, and then once we're on the network, we just curl and run a bash script which does the rest.

The same goes for Windows.

We install the operating system using an automated answers file called autounattend.xml. There's a nice little generator here which you can use if you don't want to have to set up a whole Windows server to set up unattended installations. You generate that XML file, and you can also use that XML file to bootstrap the config.

Again we use it as little as possible, because writing automations as XML elements is kind of a pain. So we essentially just set up a scheduled task to run the next stage of the config, we install the network driver, we import some registry settings, and we reboot. That's it. The rest of it is done with a PowerShell script.

The same goes for macOS.

Now, unfortunately, installing the OS and bootstrapping the config does have to be done by hand. And this is because if you want to automate a macOS installation, your two options, more or less, are enterprise device management solutions, which cost a lot of money and mean that you have to have a macOS server around to control and orchestrate the servers. But if you don't want to use one of those enterprise solutions, what most open systems that are faced with this problem end up doing is to throw OpenCV at the problem. I've seen several projects use OpenCV to OCR the setup wizard, which is... it's certainly a bold strategy. It's not really for me.

What I decided to do instead is just install the OS by hand, and pipe curl into sh to kick off the config management process. And this is something that we only really have to do once, because we do it once, and then we take a snapshot of it, and then we never have to do it again, at least until the next version of macOS comes out.

So this bootstrap script just does a handful of minimal things: it enables automatic login, it sets up a LaunchAgent to ensure that we can run our own code on each boot, and then it does a handful of other things which it honestly doesn't really have to do in this script. We could probably do these things in the zsh script which we then curl and run. And that's where the remainder of the work is done.

So looking forward, some things that we'd like to do with this system.

The first is to decouple it from Servo. So we built this CI system quite organically over the past 12 to 18 months, and we built it around Servo's needs specifically, but we think this system could be more broadly useful for other projects. We'll just have to abstract away some of the Servo specific bits, so that it can be more easily used on other projects, and that's something we're looking into now.

Something else that we'll have to do sooner or later is add support for macOS runners on Apple Silicon, that is ARM64, and the reason we have to do this is that macOS 26, which is the most recent version of macOS that came out in September, that's just a couple months ago, that is the last version of macOS that will support x86 CPUs. And at the moment, our macOS runners run on x86 CPUs, on the host and in the guest.

This is a little bit complicated because at the moment, our macOS runners actually run on Linux hosts, using a Linux-KVM-based sort of Hackintosh-y kind of solution. And there is no counterpart for this for arm64 hosts and guests, and I'm not sure there ever will be one. So we're going to have to port the system so that it can run on macOS hosts, so we can use actual Mac hardware for this, which is easy enough to do, and that's in progress.

But we're also going to have to port the system so it can run with other hypervisors. And this is because, although libvirt supports macOS hosts, the support for the macOS Hypervisor framework and Virtualization framework is not mature enough to actually run macOS guests in libvirt. And I'm not sure how long that will take to develop, so in the meantime, we've been looking at porting the system so that when you're on a Mac, you can run with UTM instead, and that's been working fairly well so far.

We're also looking at porting the system so that it can run with Forgejo Actions and not just GitHub Actions. So Forgejo Actions is an open alternative to GitHub Actions that tries to be loosely compatible with GitHub Actions, and in our experience, from experimentation so far, we found that it mostly is loosely compatible. We think we'll only have to make some fairly minor changes to our system to make it work on both CI systems.

That said, this CI system could potentially be more broadly applicable to other CI services as well, because virtual machine orchestration is something that we haven't really seen any CI services have a great built-in solution for. So if this interests you and you want to use it on your project on some other CI service, then we'd appreciate knowing about that, because that could be something we would explore next.

The remaining ideas are things that I think we could look into to make our runners more efficient.

The big one is autoscaling. So at the moment when you set up a server to operate some self-hosted runners, you essentially have to statically pre-configure how many runners of each kind of runner you want to be kept operating. And this has worked well enough for us for the most part, but it does mean that there's some kind of wasted resources sometimes, when the moment-to-moment needs of the jobs that are queued up aren't well fitted to the composition of your runner configuration. So if we had the ability to dynamically respond to demand, or some kind of autoscaling, I think we could improve our runner utilization rates a little bit, and sort of get more out of the same amount of runner capacity, the same amount of server capacity.

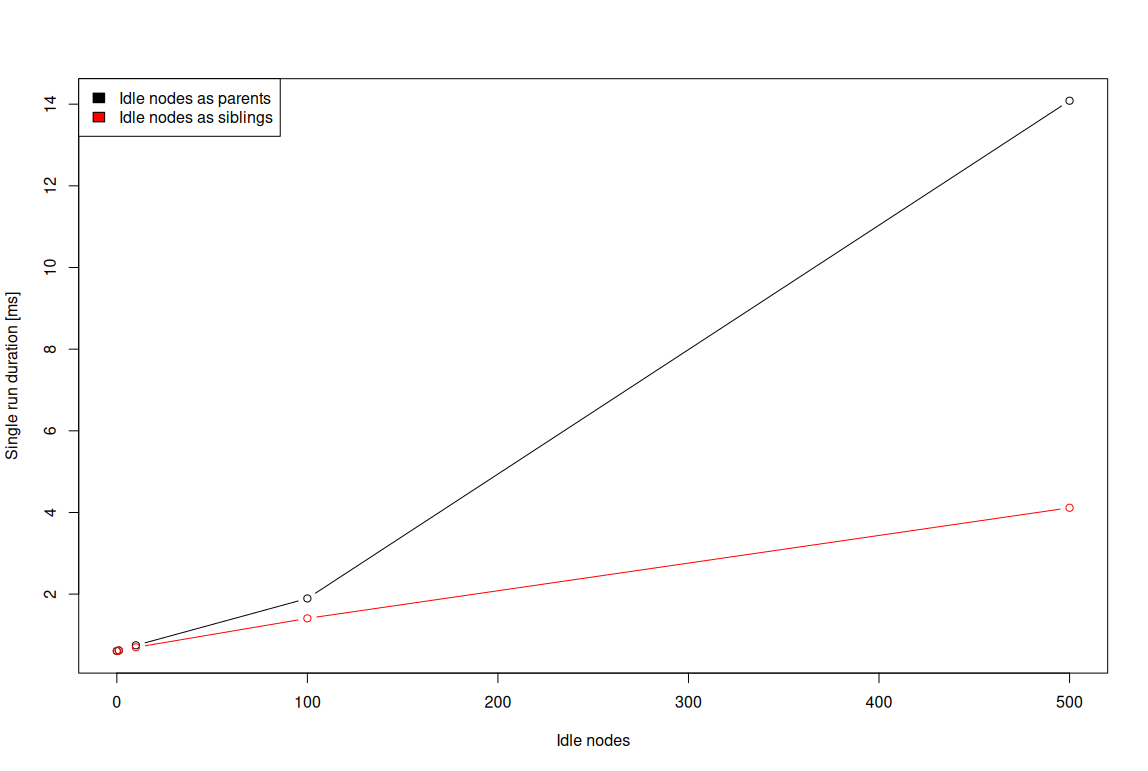

There's a couple ideas here, also, about reducing boot times for the runners, which can be quite helpful if you have a big backlog of jobs queued up for these servers, and this is because time spent booting up each runner, each virtual machine, is time that cannot be spent doing real work.

So two ways we can think of to reduce these boot times are, to have hot spares ready to go, the idea being that, if you can spin up more runners than you actually intend to run concurrently, and just have them sitting around, then you can kind of amortize the boot times, and sort of get the boot process process out of the way. And the way you do this is by spinning up a whole bunch of runners, say maybe you spin up like twenty runners, even though you only intend to run four of them concurrently.

And what you do is you give these runners a token amount of RAM to start with. You give them like one gig of RAM instead of 16 or 32 gigs of RAM. And then when a job comes in, and you actually want to assign the runner out so that it can do the work, then you dynamically increase the RAM from one gig, or that token amount, to the actual amount, like 16 gigs or 32 gigs. And this should be fairly easy to do in practice. This is actually supported in libvirt using a feature known as memory ballooning. But there are some minor caveats, like you do lose the ability to do certain optimizations, like you can't do huge pages backing on the memory anymore. But for the most part, this should be fairly technically simple to implement.

Something that could be more interesting in the longer term is microVMs, things like Firecracker, which as I understand it, these microVMs can sort of take the concept of paravirtualization to its logical extreme. And what it means is that on kernels that support being run as microVMs, you can boot them in like one or two seconds, instead of 20 or 30 or 60 seconds. And this could save a great deal of time, at least for jobs that run on Linux and BSD. I don't know if I said Linux and macOS, but I meant Linux and BSD.

So yea, we now have a system that we use to speed up our builds in Servo's CI, and it works fairly well for us. And we think that it's potentially useful for other projects as well.

So if you're interested to find out more, or you're interested to find out how you can use the system in your own projects, go to our GitHub repo at servo/ci-runners, or you can go here for a link to the slides. Thanks!

article > section:not(#specificity) {

position: relative;

display: flex;

flex-flow: column nowrap;

padding: 1em 0;

}

article > section:not(#specificity) > * {

flex: 0 0 auto;

}

article > section:not(#specificity) > ._slide {

max-height: 50vh;

flex: 0 0 auto;

position: sticky;

top: 0;

text-align: center;

}

article > section:not(#specificity) > ._slide > img {

max-width: 100%;

max-height: 50vh;

}

article > section:not(#specificity) > ._spacer {

flex: 1 0 1em;

}

Migrating Unpacked directory installation from //chrome to //extensions

Migrating Unpacked directory installation from //chrome to //extensions Moving .crx installation code from //chrome → //extensions

Moving .crx installation code from //chrome → //extensions

![Decision jobs

- Prepend a job that chooses a runner label

1. let label = runner available?

| yes => [self-hosted label]

| no => [GitHub-hosted label]

2. $ echo](https://www.azabani.com/images/servo-ci/mpv-shot0048.jpg) [self-hosted label]

| no => [GitHub-hosted label]

2. $ echo " /> [self-hosted label]

| no => [GitHub-hosted label]

2. $ echo " /> [self-hosted label]

| no => [GitHub-hosted label]

2. $ echo "label=${label}" | tee -a $GITHUB_OUTPUT

- Use the step output in runs-on

runs-on: ${{ needs.decision.outputs.label }}

- But two decisions must not be made concurrently">

[self-hosted label]

| no => [GitHub-hosted label]

2. $ echo " /> [self-hosted label]

| no => [GitHub-hosted label]

2. $ echo " /> [self-hosted label]

| no => [GitHub-hosted label]

2. $ echo "label=${label}" | tee -a $GITHUB_OUTPUT

- Use the step output in runs-on

runs-on: ${{ needs.decision.outputs.label }}

- But two decisions must not be made concurrently">

- runs-on: ${{ needs.decision.outputs.label }}

runs-on: 6826776b-5c18-4ef5-8129-4644a698ae59

- Initially do this directly in the decision job (servo#33081)" />

- runs-on: ${{ needs.decision.outputs.label }}

runs-on: 6826776b-5c18-4ef5-8129-4644a698ae59

- Initially do this directly in the decision job (servo#33081)" />

- runs-on: ${{ needs.decision.outputs.label }}

runs-on: 6826776b-5c18-4ef5-8129-4644a698ae59

- Initially do this directly in the decision job (servo#33081)">

- runs-on: ${{ needs.decision.outputs.label }}

runs-on: 6826776b-5c18-4ef5-8129-4644a698ae59

- Initially do this directly in the decision job (servo#33081)" />

- runs-on: ${{ needs.decision.outputs.label }}

runs-on: 6826776b-5c18-4ef5-8129-4644a698ae59

- Initially do this directly in the decision job (servo#33081)" />

- runs-on: ${{ needs.decision.outputs.label }}

runs-on: 6826776b-5c18-4ef5-8129-4644a698ae59

- Initially do this directly in the decision job (servo#33081)">

![Uniquely identifying jobs

- Tie them together by putting the <UUIDv4> in the name:

name: Linux [${{ needs.decision.outputs.unique-id }}]

name: Linux [6826776b-5c18-4ef5-8129-4644a698ae59]

- Query the CI service API for all jobs in the workflow run

- Check the status of the job whose name contains

[${{ needs.decision.outputs.unique-id }}]

- Yes, really, we have to string-match the name :)))](https://www.azabani.com/images/servo-ci/mpv-shot0054.jpg) in the name:

name: Linux [${{ needs.decision.outputs.unique-id }}]

name: Linux [6826776b-5c18-4ef5-8129-4644a698ae59]

- Query the CI service API for all jobs in the workflow run

- Check the status of the job whose name contains

[${{ needs.decision.outputs.unique-id }}]

- Yes, really, we have to string-match the name :)))" /> in the name:

name: Linux [${{ needs.decision.outputs.unique-id }}]

name: Linux [6826776b-5c18-4ef5-8129-4644a698ae59]

- Query the CI service API for all jobs in the workflow run

- Check the status of the job whose name contains

[${{ needs.decision.outputs.unique-id }}]

- Yes, really, we have to string-match the name :)))" /> in the name:

name: Linux [${{ needs.decision.outputs.unique-id }}]

name: Linux [6826776b-5c18-4ef5-8129-4644a698ae59]

- Query the CI service API for all jobs in the workflow run

- Check the status of the job whose name contains

[${{ needs.decision.outputs.unique-id }}]

- Yes, really, we have to string-match the name :)))">

in the name:

name: Linux [${{ needs.decision.outputs.unique-id }}]

name: Linux [6826776b-5c18-4ef5-8129-4644a698ae59]

- Query the CI service API for all jobs in the workflow run

- Check the status of the job whose name contains

[${{ needs.decision.outputs.unique-id }}]

- Yes, really, we have to string-match the name :)))" /> in the name:

name: Linux [${{ needs.decision.outputs.unique-id }}]

name: Linux [6826776b-5c18-4ef5-8129-4644a698ae59]

- Query the CI service API for all jobs in the workflow run

- Check the status of the job whose name contains

[${{ needs.decision.outputs.unique-id }}]

- Yes, really, we have to string-match the name :)))" /> in the name:

name: Linux [${{ needs.decision.outputs.unique-id }}]

name: Linux [6826776b-5c18-4ef5-8129-4644a698ae59]

- Query the CI service API for all jobs in the workflow run

- Check the status of the job whose name contains

[${{ needs.decision.outputs.unique-id }}]

- Yes, really, we have to string-match the name :)))">

).

).

. What things? Anything JavaScript makes possible.

. What things? Anything JavaScript makes possible.